“Makes fun of the Easter Bunny / Reunites with dad / Goes to pololoco for chick . . . plays basketball; crosstraining? Hungry again, narrator says: more fried chicken”

Those are the writer’s notes on Saturday night. It’s preliminary sketching for a piece he has to write for one of the wire services, about the marketing of boxing pay-per-view attractions. They were supposed to be out of this business of network advertising after the last one went so terribly, but then a reader used the word “hater” in an email to the editor, and now the writer has to redeem the service. Coincidences abound, thinks the writer, as he edits what he will record about what he is watching because his editor is a goaltender who doesn’t take to combat sports and holds it against every article that treats them, and so he’s going to have to shoot for the corners if any of this story will make it to print.

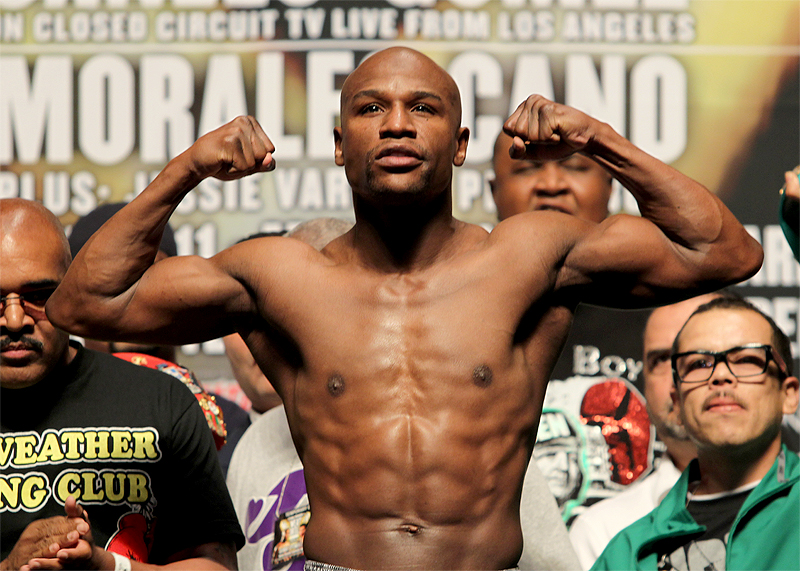

The writer sits on the opposite side of a couch from his girlfriend’s son, who is 15 and typical. He says he is a fan and an athlete; he attends the boxing gym – when his dad takes him – but mostly goes upstairs and plays basketball, as that is where the girls, and so the better athletes, congregate. His mom says he is a JV player on Mayweather’s “Money Team,” forgetting the captain for about half of each year.

“Floyd’s right, you know?” the kid says to the room. “The Easter Bunny laying eggs is dumb.”

The writer makes a note about Floyd’s grasp on the obvious, wondering if the obvious vulgarly expressed was as alluring when he was 15. He decides it was. Floyd’s primary appeal may lie in his saying things others won’t. It resonates with a teenager who sees conformists getting invited to parties that snub nonconformists.

“‘Floyd and I’s bond is unbreakable’?” the writer notes, transcribing what Mayweather’s fiancée says on the first of two HBO programs about Mayweather. “Loyalty?”

“Even women want to stay on the Money Team,” the kid says to the room. “Ms. Jackson knows she’s got it better with Floyd.”

“‘Ride-or-die’?” the writer notes with an asterisk, to remind himself to see what that means later, or maybe think of a gentle way to ask his girlfriend’s son.

“I’m still going strong!” Mayweather shouts at the camera. “I still look good and young. Feel strong. Still got big muscles. Still flamboyant. Still shit-talking. Fly whips, big mansions!”

The kid smiles at the television and thinks Floyd had to say that, cued by the producer. Like a switch. For the haters. It makes white people, the Republicans, buy fights to see Floyd get beat up. But Floyd never loses. He’s too smart.

“There’s 50!” the kid says to the room. “He’s a genius.”

The writer changes his posture, instantly defensive. This derelict “a genius”? Isn’t he the guy who got rich singing it was somebody’s birthday? “WTF?” the writer scribbles in large letters.

“That’s crazy,” the kid says. “I thought 50 was out, like, every night.”

The writer’s previous posture returns. “Curtis Jackson as an introvert and artist . . .” he writes. Actually hadn’t crossed his mind.

“Floyd’s got’em again,” the kid says. “How you gonna call yourself ‘loyal’ and fire your own uncle, Cotto? Floyd’s real. He can only act like he doesn’t care a little. Then he brings the truth.”

He’s not a good actor either, the writer thinks. A pro shouldn’t get tired while on set. “Half-assed villain,” the writer notes.

“Hey, it’s the nerdy dude from the Tupac movies!” the kid says. “I didn’t know they were doing two ‘24/7s’.”

“‘On Floyd Mayweather’,” the writer puts at the top of a new page in his notebook, and underlines it.

The kid watches Floyd yell at his father and throw his ass out of the gym. That’s what you get. You show up, now, when your boy is famous, and you try to take over his gym for the cameras, and you dis your own brother by saying you did everything? Throw his ass out.

“Mayweather’s dad / cussing him out / says he’s nothing / former drug dealer / comes back for control,” the writer notes, wondering how much of Floyd’s point, here, would be lost in exposition.

The kid checks his cell. He’s bored. The nerdy dude is making Floyd look weak.

“King and Malcolm X!” the writer says to the room. “You’re no civil rights hero for going to jail, Floyd!”

“Malcolm wasn’t what y’all would call a ‘civil rights hero’ when he went to jail, either,” the kid says. “Was he?”

“No one would never understand me,” Mayweather says to Michael Eric Dyson.

“I understand you,” the kid says. “Because nobody understands me.”

No 15 year-old thinks anyone understands him, the writer thinks. He gives others what Oscar Wilde called the benefit of his own inexperience. “‘Nobody understands me’ / same thing Tyson said,” the writer notes; “they capture the disconnectedness of the American teenager”

“Floyd’s making the professor the student,” the kid says. “The nerdy dude just said Floyd was intelligent and well-spoken. Put him on the Money Team, Floyd.”

“‘School will always be there’?” the writer notes. How can he say that to a college professor? how can he be so dismissive? how can the professor just sit there and take it, smiling? “wtf?” the writer scribbles again.

“That’s what a man does, dude,” the kid says. “Floyd had a family to take care of. He made the man’s choice.”

Mayweather leans over and shakes Dyson’s fingers, and the camera swoops upwards.

Bart Barry can be reached at bart.barrys.email (at) gmail.com.