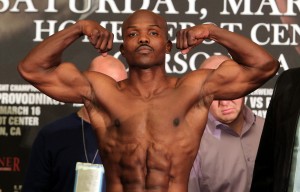

American welterweight Timothy Bradley was knocked-out at 2:33 of round 1 by Russian Ruslan Provodnikov, Saturday at Home Depot Center in Carson, Calif. Bradley began a right cross at the moment Provodnikov did, and while Bradley’s grazed harmlessly past, Provodnikov’s struck flush. Bradley buckled, fell forward, clutched Provodnikov round the yellow letters on the seat of his trunks, then fell to his knees and black gloves. Bradley rose, backpedaled, fell, rolled over, and rose again with the lunatic smile a man wears when no signal his brain sends down the spinal cord is obeyed by his lower body.

If consciousness is an awareness by the mind of itself and the world, Bradley was not conscious for most of the 33 minutes of fighting that followed. But in what variable moments of consciousness he experienced, Bradley sent communiques enough to the learned muscles of his body to decision Provodnikov by unanimous scores of 114-113, 114-113 and 115-112 and retain the WBO welterweight belt he took from Manny Pacquiao in June. Treated to valorous a display as an athlete can make, the sparse Home Depot Center crowd booed loudly the judges’ deciding in favor of the champion.

And there was Timothy Bradley, bouncing in his corner before the decision, trying to make a spirited sight of his readiness and fitness, showing Provodnikov he was not tired but anxious to come out and make war in the final round, except that the final round had come and gone minutes before, and Bradley seemed to have no idea of it. He was not in his right mind. If you told Bradley on Sunday morning he fought valiantly, did his level best, but finally got knocked-out by a well-fisted Russian who wore him to a nub at the end, Bradley would have had to go find his belt, if he even remembered where he put it, to be sure you were wrong.

Bradley is frailer than his detractors know. In 2011, I spoke with him in the Southwest hangar of the Detroit Metro Airport seven hours after he beat Devon Alexander, and the first thought I had as he shuffled anonymously along the gleaming tile hallway, taking tiny steps, no entourage in tow, his left eye shuttered, his face small and dark, was: “God, he looks fragile.”

The same could be said of him as he sat in a wheelchair beneath the MGM Grand dais last year after going more rounds with Manny Pacquiao than Oscar De La Hoya did, or Ricky Hatton did, or Miguel Cotto did – this must not be forgotten – and after the greatest moment of his career, one an entire industry then conspired ghoulishly to snatch from him. The same could be said of Bradley on Saturday night as he stood wideyed and confused, genuineness and goodness still shining through concussion’s miasma, and admitted he did not recall what he said three seconds before.

Timothy Bradley gives more than he has to every fight; he is ill-equipped for the combat he makes. He is a man with one knockout victory in six years who went for the knockout repeatedly, Saturday, against an opponent who’d rendered him senseless in their first three minutes together. Ruslan Provodnikov showed Bradley’s large flaws: He does not move his head until he is on an opponent’s chest, his balance is often not good as he believes, and his power at welterweight is a fraction his confidence in it. Bradley fights rather like what he is: a man whose teachers believed conditioning was more important than defense.

In the final 15 seconds of round 6, Bradley and Provodnikov threw 56 punches at one another, in as feral a display of desire and conditioning as can be seen in a prizefighting ring. Provodnikov threw many of his punches head-down and landed many more than Bradley did, head-up. Bradley needed to see Provodnikov to punch him, and that was difficult with his eyes scattering like brown marbles in sockets of polished obsidian. Provodnikov knew without having to look where Bradley’s chin would be, which allowed him, at various remarkable moments Saturday, to move his head well out of Bradley’s range as he put his wonderfully leveraged right fist in the geometrical center of Bradley’s face.

But promoter Top Rank is not yet rid of its Bradley problem, and Bradley’s flowering resentment, and how history will judge its catalyst, is to be a problem indeed. When Bradley went down in the final seconds of round 1 then got up, fell backwards, and landed on his shoulder at an angle obtuse enough to separate it, I thought of what Top Rank’s peerless matchmaker once said after an early undercard match when a local favorite got dropped by an unknown: “Nothing surprises me.” Provodnikov did exactly what was expected of him, and if he did not permanently alter the trajectory of Bradley’s career, Saturday, he likely will in the rematch Bradley will have to make long before he is given the payday he was promised if he beat Pacquiao, which he did.

We booed Bradley afterwards, again, in his home state this time, despite his making combat for a half hour his brain was too scrambled to record – booed him because three professional judges agreed he won another close fight. Bradley may forgive us, though he should not, but he will not forget, and he should not. He is a greater man than he is a fighter, and he deserves better judges than what we are.

Bart Barry can be reached at bart.barrys.email (at) gmail.com