Garcia, Lopez, Bearden and resilience

DALLAS – Thirty five miles due west of American Airlines Arena, where Oxnard’s Mikey Garcia unpicked Puerto Rican Juan Manuel Lopez Saturday, there is a bold and colorful exhibition of 20th century American artist Romare Bearden’s work. It is called “A Black Odyssey.” Its collages and cut-paper works are vibrant depictions of acts that were necessarily intimate, vile and lunatic, acts captured in historic prose by Homer. That such acts led to such words led to such visual art is a testament of sorts to the species’ resilience.

Our startling recuperative powers felt like a theme last weekend. To see Garcia on Friday and the discomfort the sight of him caused others, specifically his octogenarian promoter Bob Arum, a man who, for all his reassuring words publicly uttered during and after Garcia jeopardized his fight with Lopez, did not even look at Garcia when he returned from an hour of admitting there was no way to lose what two pounds stretched between his desiccated body and the featherweight limit, to see Garcia’s wretched demeanor, a combination of shame and shame weakened, like the rest of him, by hunger, was to wonder how such a man would summon reserves enough to rise from bed the next day – much less make violence with a former world champion in the evening.

Yet there was Garcia 33 hours later, a transformed man, or at least a returned one, a person reassured enough to stand directly in front of another world class fighter and do everything with a confidence that is Garcia’s most noticeable quality at ringside. Order was restored by a man who feels orderly, a man who absorbs others’ teachings and heeds others’ carefully worded observations and places his right cross elegantly.

There is an ecosystem in boxing, fragile as it is small, one that relies on a premium network providing meaningful programming to its audience, in the form of championship fights, one that relies on fighters arranging their calendars such that on the day or three of every year they perform they are at or very near their top physical capabilities, or else willing to be victimized by men who are, and all that was imperiled by Garcia’s weighing 128 pounds Friday afternoon.

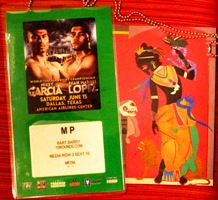

When Arum shuffled to the podium and declared the title fight cancelled and then departed nearly alone while his matchmakers and publicists continued to speak to HBO programmers and others, it was a reminder, too, of how little about the prizefighting industry we know or get told. This was not lost on the media; few of what could be called reporters remained after the initial weights were read and Mikey Garcia strode on the sunbleached walkway outside American Airlines Arena.

The Romare Bearden exhibition in Fort Worth is the sort of pleasant surprise in which the Amon Carter Museum of American Art specializes. Southernmost destination in a triangular mall that features better known collections at The Modern and The Kimbell, Amon Carter, for being committed to American art alone, finds itself liberated to make original exhibitions – like bright construction-paper collages of black figures reenacting Odysseus’ homewards journey – its larger neighbors might not. If there are parts of the Bearden exhibition that remain partially inexplicable, Bearden’s talent for shape and color and narrative remains uncompromised. And when such expressive colors as Bearden’s are juxtaposed with Homer’s uniquely pitiless descriptions, blood brought by steel and leaked always in a wine-dark sea, one is startled such art came of such depredations, that our species recuperated enough to make visually pleasing depictions of something described in “The Iliad” thusly:

The famous spearman struck behind his skull,

just at the neck-cord the razor spear slicing

straight up through the jaws, cutting away the tongue –

he sank in the dust, teeth clenching the cold bronze.

The Bearden exhibition was a fair way to prepare oneself for what he expected to happen later to Juan Manuel Lopez and did happen to him. Juanma, once the future of promoter Top Rank’s stable and celebrated as Mikey Garcia is celebrated now – though with a larger and more reliably rabid following, especially when endorsed continually and publicly by Felix Trinidad, as Juanma was and fellow Puerto Rican Miguel Cotto was not – was there to be felled and sacrificed in the erection of a new flawless promotional creation, though ultimately not free of flaws as hoped or promised.

Juanma Lopez, once accurately described by an insider as “a world-class dissipater,” nevertheless made the contracted weights for his fights, whatever had to be done – which is not to accuse of lollygagging Garcia, a man who complained of his eyes being too poorly lubricated Friday to blink without discomfort.

In black bugeye shades and a pumpkin skull cap and saddle jacket, there was Juanma at ringside Saturday, two hours before the opening bell would ring on the last meaningful match of a career that would be excellent by most other standards – there to escort his wife to her ringside seat and sit beside her through preliminary bouts. It is an interesting thing these Puerto Rican fighters do, for Cotto does it as well: Wander through an arena’s worth of people hours before a gladiatorial spectacle that anticipates their consciousness sacrificed, or another’s, or worse.

It is a reminder they are sportsmen, craftsman at something that is beastly, more than warriors. Their perspective is a healthier one than the Mexicans with whom they form our sport’s best rivalry.

Bart Barry can be reached at bart.barrys.email (at) gmail.com