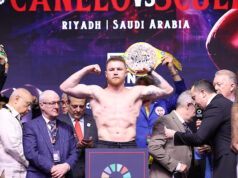

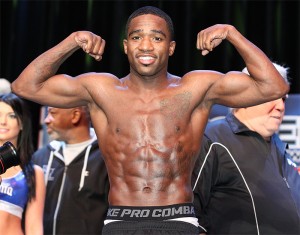

Saturday in Brooklyn two of prizefighting’s reliably unlikable personalities spent 36 minutes punching one another, much to the delight of those who watched them do it. Cincinnati’s Adrien “The Problem” Broner decisioned Brooklyn’s Paulie “Magic Man” Malignaggi by split scores of 117-111, 115-113 and 113-115 in a match for some welterweight title or other. All the cards were about right, depending on a judge’s preference for accurate counterpunching or jittery busyness, and if the fight was not a historic donnybrook, it was nevertheless a sight much greater than what its belligerents’ prefight antics anticipated.

The match was also the type likely to be closer on television than at ringside, where punch quality can be heard, making Broner’s significantly harder punches substantially more influential on judges – a species into whose minds Chuck Giampa once tantalizingly led us. As Malignaggi is a television fighter in numerous senses of the word now, it was also a fight close enough to make him bellow about a conspiracy, á la his antics in Texas four years ago, and convince the tiny minority of aficionados who are his partisans the entirety of prizefighting’s socioeconomic system would be stacked against a fighter from the tiny hamlet of New York City. The decision was correct, just the same; Broner fought better than Malignaggi, according to any creditable definition of the verb “to fight.”

It’s not until you settle into viewing a match contested by two persons for whom you feel no affection whatever that you understand what an appeal such spectacles hold. The only wish many aficionados had for Saturday’s main event was that it continue indefinitely; so long as Malignaggi had enough energy to sting Broner, or stall his attack long enough to embarrass him with his quicker wit and tongue, or at least prevent himself from being beheaded by a left-hook counter, the spectacle could have proceeded for another hour or two without the television audience asking for its end. The fight was entertaining in the way a fight can be when its observers care not a whit who wins or loses so long as both men get hit in the face often as possible.

Malignaggi has never been likable to a fraction so many people as have been told he’s likable to everyone but them; Paulie is a neighborhood hero with the great fortune of being from a neighborhood in NYC. Were someone with a squeaky voice, sideways cap atop ghoulishly dyed hair and career knockout ratio below 20 percent from anywhere else in the country, nay the world, he’d have been forgotten after Miguel Cotto victimized him in 2006. So few good boxers come from such a great media market, however, we’ll never be rid of Malignaggi till he is rid of gloves, which is a shame because he’s already a more enjoyable commentator than ever he was a fighter.

Cotto is a good place to look at what boxing has in Broner. Some seven years ago, when Malignaggi was 25 years-old and undefeated, Cotto dropped him in round 2, shattered his orbital bone and beat him savagely enough not one of the three official judges in Madison Square Garden was able to give a majority of rounds to the hometown fighter. And if memory serves, the infrastructure of Malignaggi’s face was too fully sabotaged for him to uncap a signature postfight speech like Saturday’s.

Broner, in other words, did not do nearly well against Malignaggi as Cotto did, and while there are plenty of reasons for this – and Broner’s leaping two weight classes mustn’t be forgotten, and should be praised – it still says something about the state of today’s game. There is more hyperbole about Broner now than there was about Cotto then, despite their having the same number of prizefights at the time of their confrontations with Malignaggi, who is decidedly not the cocksure fighter he was when he threw hands with Cotto. Broner, boxing tells itself, is the future of the sport, and with a heavyweight division that does not belong on American television, what choice does anyone have but to believe it?

Broner is very good, and this era is shaping up to be pretty poor. The divisiveness between the sport’s only relevant promoters, now each with the vacuum seal of its own network to ensure undesired realities do not interfere with licensing fees, has wrought little good. This era will pass and be recalled for its passing of the pay-per-view standard from one well-managed American cherrypicker to the next, and be forgotten quicker than even skeptics right now believe.

Malignaggi did remind future Broner opponents of something noted before: So long as you are punching Broner, he is not punching you. In the opening minute of round 4, Malignaggi proved this decisively by throwing some 15 unanswered punches at The Problem. Barely half of them landed, and only two, a right cross that followed a left hook, were meaningful, but what made Malignaggi’s punch reel interesting is how defensive it made Broner. After Malignaggi landed three or four tapping jabs on Broner’s lead shoulder, elbows and gloves, Broner prepared to throw a well-leveraged potshot counter, but then Malignaggi leaped back on his chest and threw his best combination of the night, and all Broner did was lean farther back before jackknifing forward to a position from which it was impossible to punch.

Broner’s calculus, that Malignaggi could not sustain the panicky rate of his fidgety assault for 36 minutes, was a fair one, and Malignaggi, in a workable eulogy for his career, faded constantly enough in the first 150 seconds of each round to let close ones, such as the ninth and 11th, get stolen from him in their final sixths.

Afterwards, Broner and Malignaggi showed their few supporters why the rest of us so enjoy seeing both of them get struck in the face.

Bart Barry can be reached at bart.barrys.email (at) gmail.com