By Bart Barry–

Saturday at MGM Grand Garden Arena, in the best fight of May 2015, so far, American Floyd “Money” Mayweather easily decisioned Filipino Manny “Pacman” Pacquiao, and more importantly, he made $100 million. Official scores went: 116-112, 116-112 and 118-110. Only one judge got right a match in which Pacquiao won two rounds, Mayweather possibly lost two rounds, and the rest were not close.

If there is a happy take-away from Saturday for our beloved sport, it is no better than this: Realizing, for once, the average pay-per-viewer drunkenly echolocates boxing telecasts like a bat – forming a picture in his mind as much from what he hears as what fills his eyes – the cocommentating crew from cable networks HBO and Showtime checked-and-balanced itself to an objective broadcast that presented the fight in its lopsided lack of glory, engendering no claims of scandal.

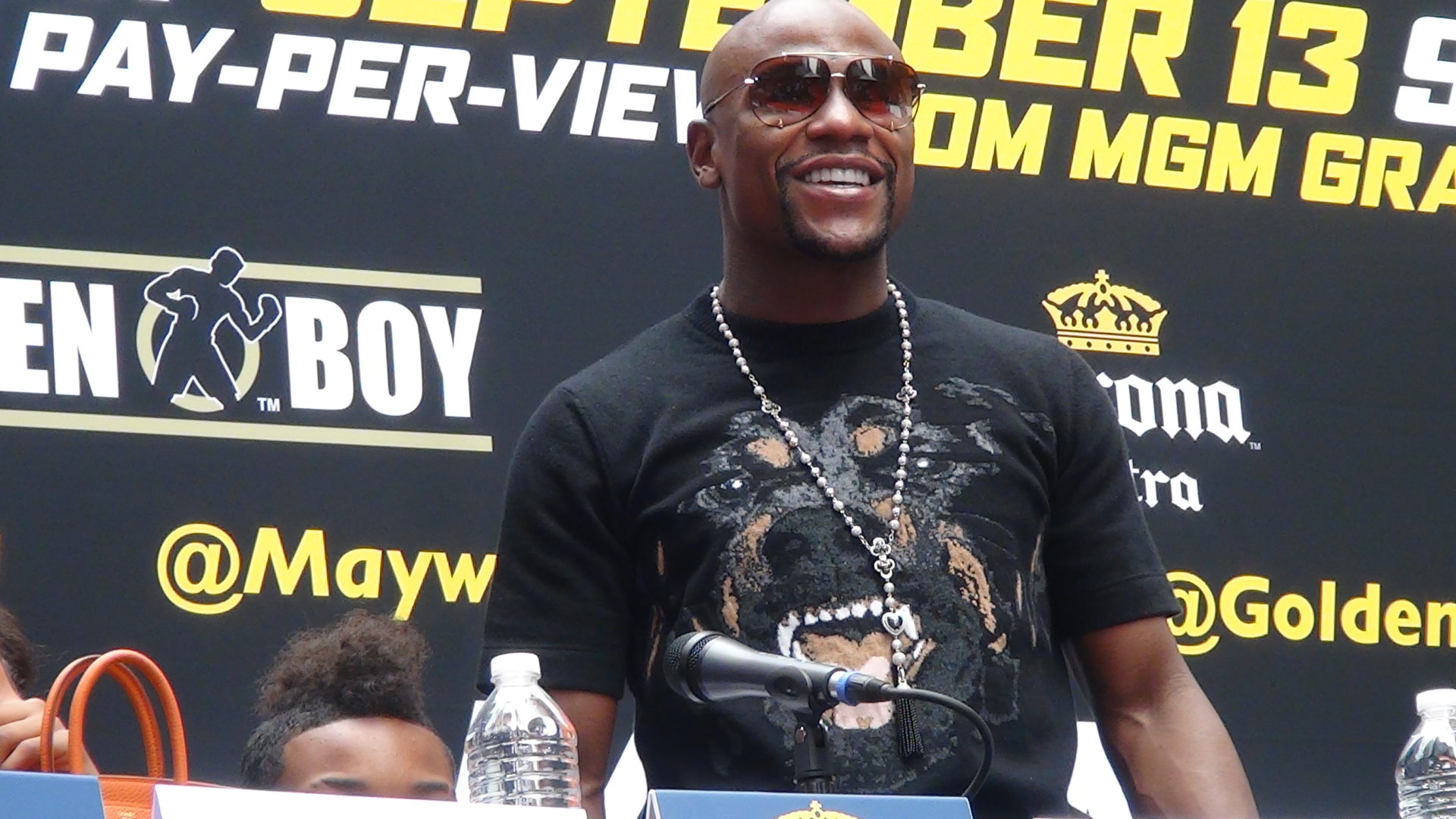

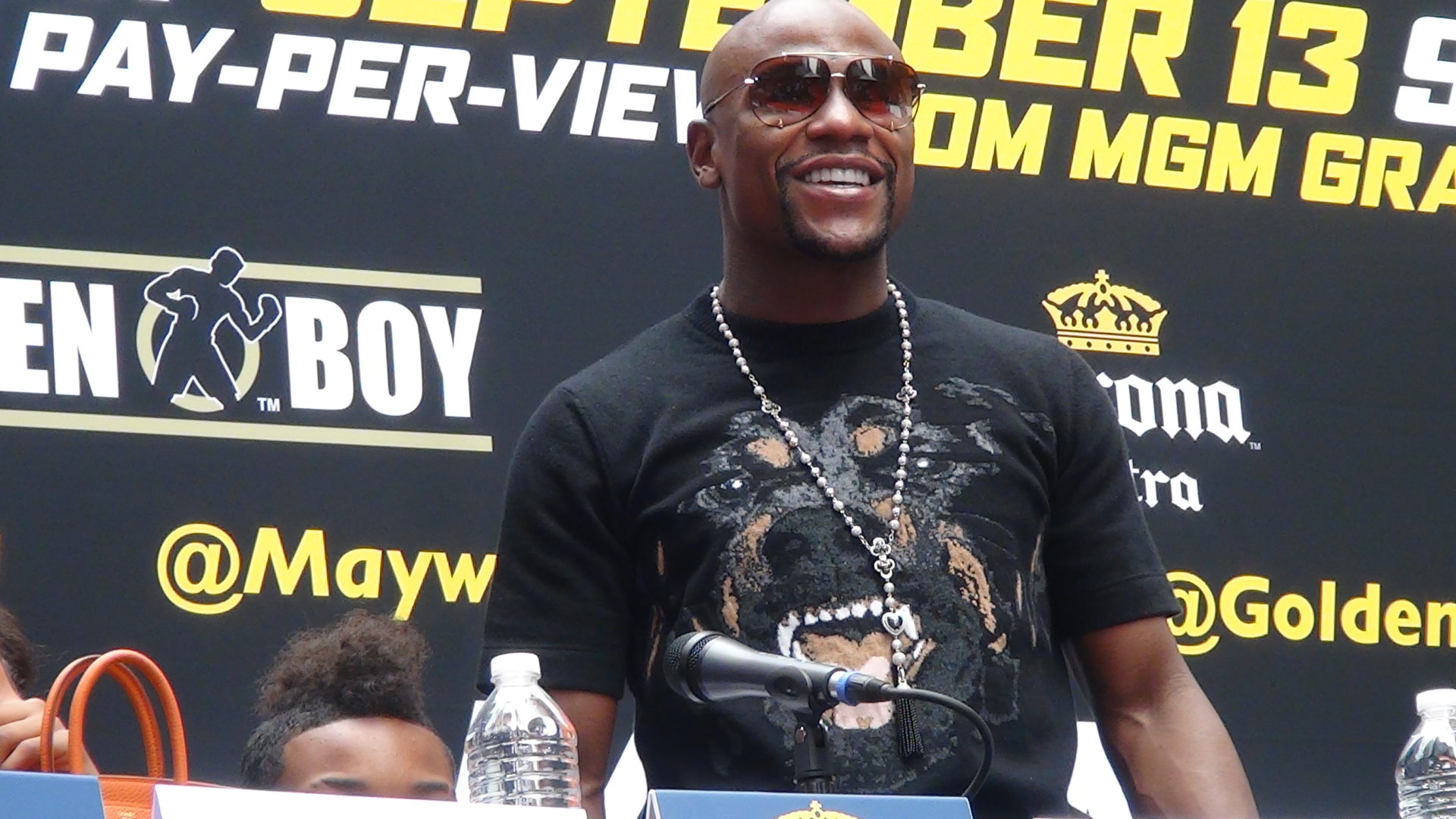

If historians return to Mayweather-Pacquiao someday, though its ultimate irrelevance is probable, it will be to mark a very talented athlete’s final vengeance on a sport he’d grown to hate deeply. There will be a montage of essential moments in this marking: Mayweather gloomily glancing down on Pacquiao’s forehead at the Friday weighin, Mayweather standing directly in front of Pacquiao with his gloves at his waist, Mayweather skipping frantically away in round 12, and Mayweather standing on a ringpost to yell at a large assemblage of people who realized they’d been had again – and this time, worst of all, by five years of their own imaginings.

Manny Pacquiao deserves no praise for his Saturday effort. He made no adjustments. He took entire rounds off. And he gracelessly claimed he won the fight afterwards and further subverted what esteem aficionados held for him, hours later, by attributing his listlessness to a shoulder injury – as if he’d not used that same shoulder to raise his arms jubilantly overhead at the Friday weighin. Coach Freddie, whose termination is likely in promoter Top Rank’s third Manny remake (since already it’s apparent the injured-shoulder gambit smells too desperate), deserves even less praise than Pacquiao does; he trained his charge for a fighter with no more dimensions than Antonio Margarito showed. Sure, Mayweather was much faster at evading counters than Roach was on the handpads, and for an injured fighter Pacquiao certainly hurled that counter right hook, didn’t he, but ultimately Mayweather used the playbook Juan Manuel Marquez wrote in 42 rounds against Pacquiao to expose exactly how little Roach actually taught Pacquiao in their vaunted educational sessions together.

Commentator Jim Lampley was right in his midfight allusion to Marquez-Pacquiao 3, the match whose second half saw Pacquiao hopelessly swim at Marquez, taking five steps where Marquez needed two, and thoughts of Marquez returned, too, in round 9 when Mayweather caught Pacquiao pure with a right cross the much larger man did not plant on, and it was a reminder why, whoever will be recalled as the greater fighter, Marquez will remain the more beloved one for showing a form of courage with which Mayweather is yet to familiarize himself.

How enormous must Mayweather have looked to Pacquiao in that opening round? Seven-feet and about 250 pounds, probably, as Mayweather’s chin was farther from Pacquiao’s anxious fists as any chin ever has been. Unsurprisingly, Paulie Malignaggi, already our generation’s best commentator, seated beside Lennox Lewis, easily its worst, was the one to distill the fight to its quintessence: Mayweather fought at his desired time and distance, and Pacquiao did not.

In round 4 Pacquiao finally caught Mayweather with a punch, countering him with a left cross the same way Marcos Maidana countered him with a right hand in September, and Mayweather put his hands up, retreated and felt what Manny had for him. Which was not much. Pacquiao fought “intelligently” and retreated himself, back to the middle of the ring, so as not to expend energy carelessly. Imagine that: Pacquiao calculated he had a better chance of outsmarting Mayweather than outworking him. It was a reminder, along with Mayweather’s considerable size advantage, of the second part that made this fight a mismatch the day it was signed: Pacquiao, since his 2010 fight with Margarito, is fractionally active as laymen think he is. Pacquiao lost a 2012 decision to Timothy Bradley because he was inactive and inaccurate. He opted for frantic activity in his fourth match with Marquez and got iced. Mismatches with punching bags got split by a rematch with Bradley in which Pacquiao, promised the benefit of every scoring doubt, fought no more than 90 seconds of each round. A kinder and wiser Pacquiao is what aficionados have been served for 4 1/2 years now.

The only chance Pacquiao had or would ever have against Mayweather is if science somehow took the wildcat demon who shredded Erik Morales nine years ago and added 20 pounds of muscle to his frame without slowing him a wink. An impossible thing, in other words, Pacquiao ever had a chance against Mayweather, and every single reader of this column knew it the night Marquez left Pacquiao in a heap, and then we chose to suspend our disbelief because a boxing promoter is good at nothing so much as legerdemain, waving crazily a Chris Algieri doll in his right hand while palming the two-headed Marquez coin in his left.

Those who surround Floyd Mayweather know he cannot imagine boxing in his absence; for Mayweather, the sport of boxing ends the day he retires. Because of Mayweather, few of us will have the presence or means to argue with him when that day comes. Against the future of boxing, then, I’ll take Mayweather: UD-49.

Bart Barry can be reached via Twitter @bartbarry