By Jimmy Tobin-

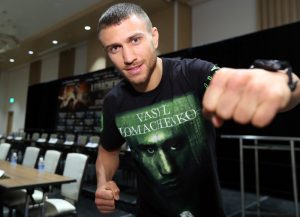

Saturday night, at the MGM National Harbor in Oxon Hill, Maryland, Ukrainian super featherweight Vasyl “Hi-Tech” Lomachenko stopped New Jersey’s Jason “El Canito” Sosa in nine rounds. The fight was over within minutes, however long it took for the end to come. It was what could become a typical Lomachenko performance: one where an overmatched opponent exercises the only power remaining to him, choosing the moment to lose rather than lament that choice’s departure over another handful of hopeless rounds.

Sosa was a good opponent, good enough to make Nicholas Walters miss the featherweight division, good enough to win a fringe title by knockout, but his haplessness was evident before even a commentary team eager to celebrate Lomachenko would have it (a whiff of danger being welcome if only to celebrate its impotence). In the first round, Sosa threw a right uppercut/left hook counter so late he appeared to be shadowboxing alone. A deep breath followed, as did a nod, and in his body language Sosa betrayed his role in the forthcoming puppetry. Sosa’s greatest attribute was a doggedness that charmed for as long as the fight did; but courage, bravery, resolve—if all they can offer is confirmation of themselves, well, then a fight losses much of that which makes it sporting.

To make too much of Sosa’s comportment is to compensate for the severity of the mismatch. There is a proselytizing quality to such talk, a propagandistic one too; and the force of those arguments reflects the strength of resistance they meet. (It should come as no surprise then, that Lomachenko’s enthusiasts are so passionate: they are railing against the most passionate fanbase in the sport, one that will never find much glory in the practice of hitting and not getting hit).

And yet much of the criticism of Lomachenko smacks of inauthenticity too, seemingly the product of a bitterness, of a frustration with Lomachenko being offered the crown without having earned it. But why get upset over praise from people whose opinions you neither share nor credit? And why act as if a fighter is responsible for what is said of him? Especially when that fighter has on many occasions tempered the highest praise he has been paid?

What can honestly be said of Lomachenko is that he is stylistically and athletically unique among peers and that he has used this idiom to tantalizing effect. Lomachenko shrinks the ring not by closing avenues of escape but by giving his opponents turning sickness, and the angles and body positioning he uses leave opponents one-handed. All the while he chips away at their bodies and resolve with combinations of varying speed and power; surprise as much as leverage his force multiplier. Excellent defensively without being defensive, the moments in a Lomachenko fight when he is not on the attack are few; that it takes Lomachenko time to force a stoppage says more about his style than his mentality (though there is surely a relationship there). One need only see how Lomachenko responded to the concentrated belligerence of Orlando Salido to recognize there is something primal beneath his artifice. And his confounding of Gary Russell Jr. which, not coincidentally, was Lomachenko’s first fight after the Salido loss, was plenty malicious.

Those who relish in destruction, however, may not shine to Lomachenko’s brand of discouragement, especially when he imposes it on men who can offer little resistance. His performances are cold in the way Gennady Golovkin’s are, in a way Sergey Kovalev’s are not. Still, there is also something appealing about a fighter who makes his opponent’s quit; who can persuade men to relinquish their shields rather than leave on them, fully aware of what shame and humiliation may await such a reasonable decision. Yet when the challenge is minimal so too is the shame. And there is the challenge to fully appreciating Lomachenko: you begin by being impressed (even spectacularly so) and your mind conjures up images of his superlative ability tested by a world-class opponent, but then you remember how likely such a contest is, and that is when something too close to ennui or futility or disappointment sets in.

Still, though only nine fights into his career and with a loss on his record, Lomachenko is in a position where already every victory increases the magnitude of a possible defeat. Expectations for Lomachenko are such that he represents one of the premier scalps in the sport—and if you agree you also agree that he is one of its premier talents because knocking off a hype job means very little. Consider, for example, what praise the first man who knocks Deontay Wilder stiff will receive, and how hushed that praise will sound in comparison to the cacophony of laughs had at Wilder’s expense.

The penalty (and reward) for such esteem is that there are already but a handful of acceptable opponents for Lomachenko. If he wanted to clean out his division like Golovkin he would come under fire in a way “GGG” never has. And could you imagine the uproar if he created the 131-pound division? If you believe Mikey Garcia is the fighter to short circuit Lomachenko, you are paying the latter a compliment. If you believe Terence Crawford is Lomachenko’s Waterloo, you are acknowledging that it will take an immensely skilled junior welterweight to hang a defeat on a super featherweight with but nine fights. And then there are those who resort to evoking the 130lb versions of Floyd Mayweather Jr. and Manny Pacquiao to bring Lomachenko back to earth—as if such measures are anything but flattering.

Lomachenko’s mystique currently exceeds his accomplishments, but how many of the compliments he is paid are greater than those bestowed by the would-be matchmakers who want to see him beaten?