By Bart Barry-

We begin with a definition of cool, or don’t, because it’s something sensed, though generational difference might alter such sensations, and we do so not so much because it’s an essential topic but because it’s a possible topic to fulfill a personally essential task: Find an enjoyable weekly subject at least tangentially related to boxing.

There aren’t as many cool millenials as cool guys from previous generations, and that may be a symptom of transition or a product of technology or it may be a function of age. The older a man gets, the less cool young men appear or maybe, again, it’s generational. Cool is unaffected, unencumbered, unburdened, confident life’ll take care of you – cool is a man making his way easily in the world. Cool isn’t a pair of sneakers or jeans or a haircolor or beard or concerns about fashion.

Here’s a timely example: As I write this, in a coffeeshop in San Antonio’s Medical Center neighborhood, across the way is a handsome guy, midtwenties, 6-foot-4, trim, skinny jeans, hoody, perfect beard, white-on-black Nikes either brand new or kempt, probably in medschool, a guy women round the shop noticed when he entered. Cool. But he’s buried in his smartphone, swiping and jabbing, and his right heel is tapping frantically under the table. Uncool. As the minutes go by he’s rolling his eyes, shaking his head, smoothing his beard, alternately glaring and chomping on gum; for all his erudition and fashion choices he’s become affected, encumbered, burdened. He’s his reasons, certainly, good ones, too, he’s got a lot on his mind, but it all manifests as insecurity, anxiety about changing circumstances that may be both adverse and powerful, which might could turn out to be wisdom – rendering the few of us in the coffeeshop who are unaffected more oblivious than cool.

But experience says that’s not how things’ll play out, and experience is why men grow cooler as they age. Legend has it, a pitch like that is how Dos Equis picked a whitebeard for its most interesting man in the world; even the coolest 25-year-old lacks the experience to be cool as the coolest 50-year-old.

Which is part of the reason our beloved sport does not have nearly the quotient of cool characters one might expect. I know this because I spent much of the morning trying to name prizefighters I’ve met who struck me as cool.

Why do such a thing?

A few weeks ago I recounted complimenting a fellow boxing writer by likening him to Shock G, someone whose music informed much of my youth but about whom I’d not had a conscious thought in decades, and this week, in the anfractuous way life winds its way, I found myself listening to Digital Underground radio on Pandora and realizing anew what a remarkable artist Gregory Jacobs (a.k.a. Shock G, Icey Mike, Humpty Hump, MC Blowfish, et al.) was, which brought me to this interview about Tupac Shakur. Jacobs is the definition of cool – unaffected, unburdened, gracious, a raconteur, easy, quick to laugh.

We meet prizefighters, especially American prizefighters, before they get a chance to become cool, methinks, when they’re still edgy from fearsome upbringings. Then they achieve success and financial security, generally two prerequisites for becoming cool however their bearers define them, but seem often to shift from the automatic anxiety of rising amongst predators to the automatic anxiety of guarding against losing what status they now enjoy.

Floyd Mayweather, cool as he was in combat, was nervous when I met him, surrounded by mountainous guards and afraid he might be tricked into saying something damning. Manny Pacquiao was pretty cool but a little too eager to please. Marco Antonio Barrera was cool but with a surprisingly predatory vibe. Andre Ward was too distrustful to be cool. Jesus “El Martillo” Gonzales was really cool, but he was my first interview, so maybe it was situational (and quite possibly it wasn’t). Roberto Duran was damn cool. Julio Cesar Chavez Jr. got increasingly cool with his victories, and as a child of privilege started on a better footing, sure, but never entirely lost his whiff of fraudulence – insecure you or circumstances might expose him.

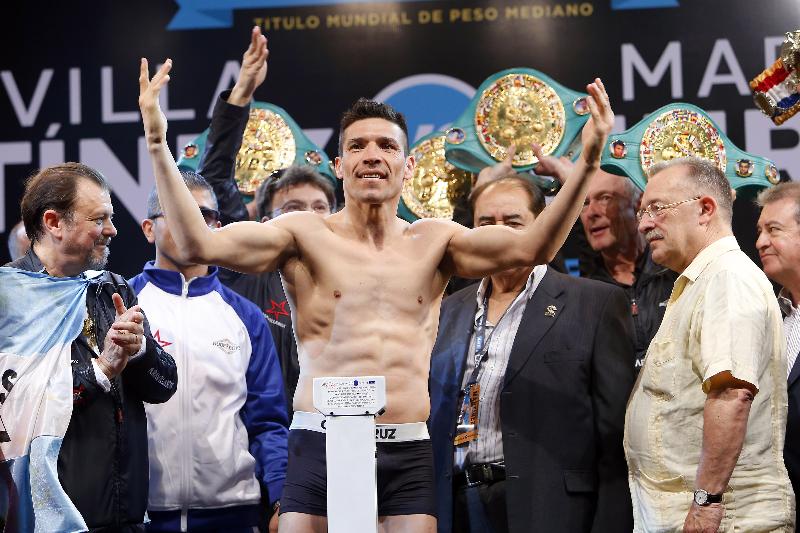

Which brings me to the coolest prizefighter I’ve met: Sergio Martinez.

A beneficiary of circumstance, perhaps, Sergio, the first time I met him, had a lot more edge than I expected from seeing him on television; he was taller and more imposing, too. We were in a postfight scrum in Houston after “Son of the Legend” retired Peter Manfredo. It was November and chilly, and there standing halfway back from the podium was the world middleweight champion in a sweater, maybe red, all alone (Rob Base: “I’m not a sucker so I don’t need a bodyguard” – another reminder from Digital Underground radio). He was there to build pressure on promoter Top Rank to risk their guy against him but would do nothing crass like storm the stage. He trusted his simple presence would indict Chavez’s titular reign.

We’d later speak on the phone a number of times, and his openness made him uniquely cool. He was unrushed and unworried. I liked him enough to chide him about his Rolling Stone-Argentina cover, Hector Camacho meets George Michael, and he laughed easily and replied in Spanish, “Look, if I were gay, I’d say, ‘I’m gay, so what?’”

Too there was the way he reacted to Julio Cesar Chavez Sr., the legend himself, at the prefight press conference for his defining fight with Chavez’s son: “Ay, Papa Chavez, you are animated today.”

Being cool is being authentic, ultimately, which summons one last irony: Trying to look cool is a sure path away from being cool.

Bart Barry can be reached via Twitter @bartbarry