By Norm Frauenheim-

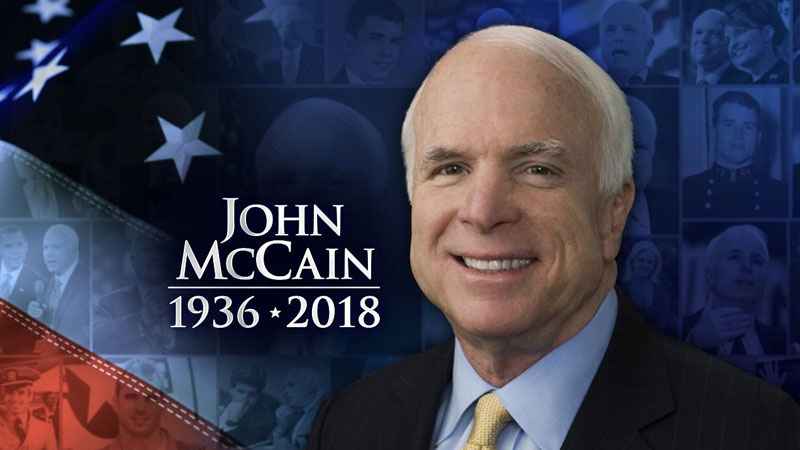

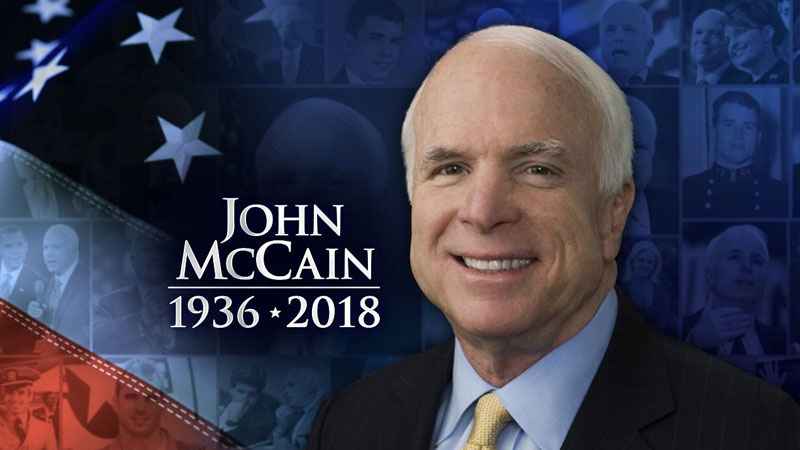

Sunday represents a sad anniversary. John McCain, statesman and soldier, died a year ago on August 25 on his Arizona ranch, about 100 miles north of an NHL arena in nearby Phoenix where ESPN was about to televise a fight card.

An opening bell was followed by 10 bells, a mournful memorial for a former amateur fighter who was called “the boxing Senator” by Bob Arum. McCain’s death wasn’t a surprise. His battle with cancer was public. And painful.

Yet, the timing was almost haunting. He died, 81, at about the same time young fighters, kids, on the undercard began to make that long walk from the dressing room to the ring. McCain identified with them. He had been one of them at the Naval Academy.

Later in life, he fought for them, a powerful advocate for young men from tough streets who knew that only their fists would fight for them.

McCain wrote, lobbied and pushed through the Muhammad Ali Act, which was introduced in 1999 and enacted in 2000.

McCain is gone, but the Ali Act is still there. It’s a small part of McCain’s many-sided legacy, seemingly made more powerful 12 months after his death. McCain stands in stark contrast with a president who did not like him and has always been quick to rip him. In life. In death.

The unfathomable depth of Donald Trump’s anger – call it hate – for McCain often makes me wonder why he hasn’t tried to rescind the Ali Act, which includes an attempt to ensure some financial transparency.

After all, Trump pardoned Jack Johnson without ever mentioning McCain or his tireless leadership in pushing for one. Trump, too, learned a trick or two in the boxing business with Don King. King lied about crowds long before Trump ever did. Yet even with Mike Tyson on the marquee, Trump drove his Atlantic City casino into bankruptcy.

Maybe, Trump is just too busy, what with Greenland and all. The sad truth, however, is that the Ali Act just doesn’t matter much. It has never been enforced the way McCain hoped it would.

Early on, it did force promoters to open up their books to fighters, who have a right to know what the gross income is expected to be. They are only negotiating for their fair share of that projected pie. That financial transparency is one reason boxers still make more money than mixed-martial artists get from the UFC, which is not subject to the Ali Act

But everything else about the legislation – conflicts of interest, enhanced safety measures – have been mostly ignored. Like his pursuit of the Johnson pardon, McCain had hoped to further empower the Ali Act with patience and time. But there was never enough interest in it from McCain’s Congressional colleagues. It’s still a law, but it’s little bit like the speed limit. Nobody pays attention to it anymore.

Two deaths in the wake of McCain’s death, however, are reason to re-energize his pursuit of some rhyme, regulation and reason instead of the usual chaos. Two of the kids with whom McCain identified are gone, dead from head trauma suffered in bouts.

First, Russian junior-welterweight Maxim Dadashev died July 23, about four days after fighting in Maryland. Two days later, Argentine junior-welterweight Hugo Santillan died from injuries sustained in a fight in Buenos Aires.

A shocked game moved on, as it always does. The attention quickly turned to what Canelo Alvarez isn’t doing and what Gennadiy Golovkin will do. There’s always another opening bell, which is another way of saying it’s business as usual.

If McCain were still alive, however, it’s fair to say he’d be calling for a thorough investigation in Maryland and an update of the Ali Act. But the Arizona Senator’s voice is long gone. What he left, however, was a blueprint, still a pathway to ensure that death never becomes usual in the boxing business.