By Bart Barry-

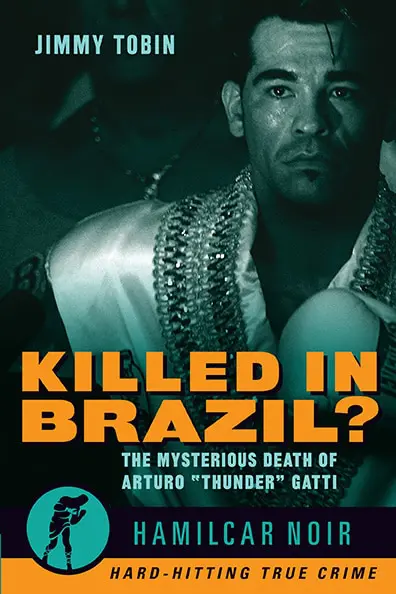

Tuesday marked the publication date of Toronto writer Jimmy Tobin’s Killed in Brazil? The mysterious death of Arturo “Thunder” Gatti (Hamilcar Publications, $10.99), the latest in a series of boxing-themed true-crime books under the Hamilcar Noir imprint. The book is excellent for the questions it asks.

I realized somewhere in the first 20 pages I care more about Jimmy’s writing than Gatti’s legacy. Maybe I knew that before I began reading Killed in Brazil? but I was not conscious of it. I revert to the first-person earlier than appropriate, here, because it affords an insight about Jimmy’s writing; he makes a reader conscious of his thoughts more and more often than most writers.

Where I find myself lost in other gifted writers’ words or stories, or simply skimming lesser writers, I find myself more aware when reading Jimmy, I find myself guessing why he made certain choices, asking how much of what I’m thinking he intended. Oftentimes I pause and answer a question he poses then decipher his reason for asking it, but when he is at his best, I find, I can’t decipher why he asked a question, and I like that discovery. I like that he’s gone in a direction I can’t explain because I know he is an intelligent writer and a thoughtful person, tender even, who writes with authority, and so, if he’s gone somewhere without leaving breadcrumbs, I know he’s invited me to a place I’d not have accessed without him.

This is not a long book but a dense one. I read it in three sittings, but I’m not a fast reader, particularly, and the more I enjoy a book the more slowly I read it. Killed in Brazil? is 71 pages long – fewer than 25,000 words – but one finishes it without a sense it needed to be any longer, and a further sense that in hands less capable than Tobin’s, in fact, it might have been shorter.

The dispassion with which Arturo Gatti gets treated is a unique appeal of this book. When has anyone treated anything about Gatti dispassionately? Ever since his first fight with Mickey Ward most of us have found ourselves effectively bullied into attributing to Gatti magical powers he often didn’t possess. For fear of getting browbeaten by his vocal champions most of us either didn’t dare or didn’t bother to write his fights with Oscar De La Hoya and Floyd Mayweather were such mismatches they evinced no courage from any of their three participants.

Tobin gives Gatti’s vocal champions, those given to browbeating, plenty of space on his pages. After affording their implications lots of credit in the book’s opening third, “Fracture”, Tobin spends the book’s middle third, “Preternatural”, doing pure boxing writing, the hooks and uppercuts and willfulness of Gatti’s career, before finishing with “Confrontation” – the book’s final third. The third third is the book’s best, as it shows us more of its author, what he values, than its two predecessor parts.

Tobin begins Part III with a commemorative mass in Jersey City, N.J., and gives the opening quote to promoter Lou DiBella as he attains an applause line about Gatti never quitting in his life and definitely not in Brazil, where Gatti’s people believed Gatti’s small Brazilian wife incapacitated, strangled and hanged her husband. Then Tobin gives the stage to television investigators and Gatti familiars and their attorneys, many American, some Canadian, and one can read their rage and certainty in every quote.

Then Tobin quietly dismisses them and just sort of wanders away to material that is much more interesting; like a man cornered in a bar by drunken fans – their chests painted in the team’s colors, their hatred for the other side distorting – who spots a noted intellectual having a quiet beer in an opposite corner, Tobin gracefully shares the actual findings of actual courts of law then begins contemplating what drove Gatti to do the thing Brazilian authorities concluded he did do, and the effect of its denial:

“When a family loses one of its own to suicide, a panic descends. This panic is rooted in the need to understand, to quarantine this act of destruction, to make it intelligible before the suffering borne of mystery spreads. This process can be quick: if the family recognized the person as capable of suicide, a clear chain of causality, of logic, can be established between the episodes of a traumatic life and its cessation. And identifying this chain brings solace. At that point of death, the dead no longer suffer. And just as important, the living don’t suffer for them. There is no more bearing witness, no more helplessness, no more hope, no more living tied to the mast in the tempest of another’s turmoil. Yes, a suicide like Gatti’s can rend a family’s chronology, forcing parents to live the nightmare of burying their child, but it is beautiful in its power to liberate. It can be heroic.”

That is a remarkable paragraph. I’ve now read it, re-read it and transcribed it, and I still don’t know if I agree with it, but it enchants me. It’s a daring turn and one Tobin makes deftly. It represents a talented writer’s choice: What it is about prizefighting that causes what brain damage might make a father and husband an addict and suicide is a worthier direction than appeasing readers who just want reassurances their favorite fighter never took his own life.

Killed in Brazil? concludes with a loving treatment of Gatti’s son and Gatti’s legacy, completing for its author a circle begun with the book’s dedication.

Bart Barry can be reached via Twitter @bartbarry