By Norm Frauenheim-

Last week, it was Triller. This week, it’s PBS.

It’s hard to go from the gutter to the Ivory Tower, but boxing knows the way. Maybe, that’s because of its curious mix of bloody brutality and ballet of footwork. At its best, it dances in and out, never far from garbage or grace.

Last week, it was the garbage, a pay-per-view Triller telecast that made heavyweight great Evander Holyfield look like an aging fool while Donald Trump played ringside commentator, praising fighters he claimed to have known. Instead, the ex-President should have been honoring dead American heroes at 9-11 Memorials.

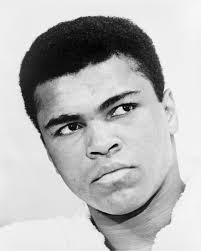

This week, grace supplants disgrace with the build-up to a four-part Public Broadcasting Service documentary about Muhammad Ali.

I’m trying to forget the image of a 58-year-old Holyfield suddenly on the canvas within just a couple of minutes of opening bell in a depressing exhibition against somebody named Vitor Belfort last Saturday in south Florida. I have a friend who likes to say that boxing is dead. The Triller telecast was like hearing last rites.

Maybe the PBS series, scheduled to begin Sunday, will help. But I’m not sure. I’ll watch, but more out of nostalgia than anything else. I’m part of the generation that grew up with Ali. As a high-school kid, I listened to the radio for the blow-by-blow accounts of his victories over Sonny Liston. As a college student, I watched him lose to Joe Frazier in 1971 on a movie screen in an old theater. All the time, I argued with my father about who was better, Ali or Joe Louis.

As a sportswriter, I met Frazier and heard how his anger at Ali was still there, hard and bitter, more than 20 years after their brutal third fight in Manila. I met George Foreman, who moved beyond his 1974 loss to Ali in Zaire. He called Joe Louis the greater heavyweight. He called Ali the greater man.

Then, I met Ali, who had moved to Phoenix in 2005 for treatment of his advancing Parkinson’s. Initially, he was playful, almost childlike. He’d play magic tricks, then draw cartoons on a sheet of paper ripped from a reporter’s notebook. From year-to-year, however, the advancing disease trapped him and silenced even him, the very man who created trash talk.

It was hard to watch.

It was even harder to not think of the punches he took.

I asked Frazier if he wondered whether his punches were responsible for Ali’s Parkinson’s.

“I don’t have to wonder,’’ Frazier said as he watched his feared left hook land during a replay of his ‘71 decision over Ali on a nearby screen during a US Olympic Committee celebration of an anniversary of the famous fight. “You see that left hand. See it. See it. That’s why he is the way he is.’’

When Foreman was making a memorable comeback that led to him regaining a heavyweight title in a victory over Michael Moorer in 1994, I asked him if Ali’s “Rope-A-Dope” tactic in ’74 might have led to Parkinson’s. Ali absorbed huge blows from the most powerful puncher of the day. The tactic paid off then. Foreman tired. Ali won, scoring an eighth-round knockout. But I’ve always wondered whether Ali paid for it later.

“Maybe,’’ Foreman told me before he launched his improbable comeback with a victory in 1989 over Bert Cooper in Phoenix.

In the years before and after he died June 3, 2016 in Phoenix, Ali’s legend has grown. He was always boxing’ biggest name, one of the sport’s original celebrities. He made sure of it with his braggadocio, social activism, opposition to the Vietnam War and his name change from Cassius Clay. He’s been gone for more than five years. But his charisma is alive. On video, it lives on in the eyes that dance like his feet. His voice is always there, a lyric like a Golden Oldie soundtrack. He had fun. And he was fearless. We can still see him. Hear him.

That’s a reason for the PBS documentary by Ken Burns, whose interest in boxing is not new. Burns’ work includes Unforgivable Blackness, the story of Jack Johnson. In Ali, he is trying to take a long look at somebody Burns calls the most important athlete in the 20th century. Jackie Robinson, Jesse Owens, Joe Louis and Jack Johnson might argue. But Ali’s role is impossible to deny. It’s huge, big enough for further documentaries, more rewrites. In boxing, at least, it is magnified by what we’ve seen – or haven’t seen lately — on Triller.

But Ali is also not bigger than boxing, although that has been suggested in some of the PBS promos. No boxer is bigger than the punches they take. Not even Ali, who landed many and took too many in a legend still growing long after the last one landed.