Juan Diaz and the Age of Impressionism

In the 1870s, a group of artists in Paris, including Pierre-Auguste Renoir, decided to stop submitting their works to the official annual exhibition of the Académie des Beaux-Arts, also called the Salon. Dubbed “Impressionists,” these brave new visionaries instead mounted eight independent exhibitions of their own, featuring works done in a new, informal style based on modern subjects of everyday life and leisure, an idea which had originally been pioneered at and rejected by the Salon.

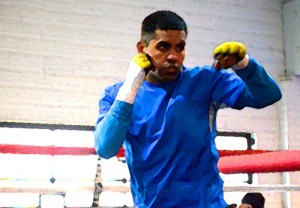

At least, that’s what the sign outside the door told me as I entered the Houston Museum of Fine Arts last Saturday afternoon after spending the morning watching former lightweight titlist Juan Diaz train and spar at his new gym, Baby Bull Boxing Academy.

I don’t know as much as I should about art. My wife and I are members at the museum, but only because we like to look at the paintings. I don’t know much about history or theory, but when we travel through the giant halls of paintings and such, I can’t help but read all the boxes of text surrounding these magnificent works.

This particular collection, The Age of Impressionism, has traveled all around the world. It was put together over time by Sterling and Francine Clark, heirs of the Singer Sewing Machine Company fortune. It features 73 paintings by artists such as our friend Renoir, as well as Édouard Manet, Edgar Degas, Claude Monet, Berthe Morisot, Camille Pissarro and Alfred Sisley and others. This was the last stop of the tour. After traveling to Tokyo, London, Barcelona, Milan, etc., etc., etc., the collection would stop in Houston before returning back home to The Sterling and Francine Clark Art Institute in Williamstown, Massachusetts.

Juan Diaz has traveled the world, too. He’s the heir to his own fortune, though, wrought the hard way and from a very young age. Diaz was born Sept. 17, 1983 in Houston, Texas to Fidencio and Olivia Diaz, a young couple from Guerrero, Mexico. When he was just eight years old, Fidencio, a rabid boxing fan, took little Juan to Willie Savannah’s boxing gym.

Diaz entered and won his first tournament at 12. At 16, he qualified for the Mexican Olympic team, but was three months too young to compete at the 2000 Summer Olympics. Later that year, with a 105-5 amateur record, Diaz decided to turn pro.

Diaz had a solid career as a professional. By the end of things, he was one of HBO’s regularly featured darlings. He won lightweight title belts and even fought two big money fights against all-time great Juan Manuel Marquez for the lineal lightweight championship. Diaz was a fan favorite during his heyday, and after the second loss to Marquez he seemed to be getting out of the fight game while the getting was still good. At age 27, with all brain and bodily functions still intact, Diaz decided to hang up the gloves and get on with the rest of his life.

But Diaz is back in boxing now. After almost three years of pause, Diaz unexpectedly returned to the ring and knocked out Gerardo Cueves in April 2013 in six rounds. Houston’s most popular fighter rounded out the year with two more wins over similar fare, knocking out Adailton De Jesus in five and going the 10-round distance with Juan Santiago.

Diaz is older now. He does not fight with quite the same frenetic energy but he still appears aggressive and hungry. At 30, he has won three straight on his way back up the ranks, and he’s still able to make the lightweight division with relative ease, something that should only help him in his effort to recapture former glory. And that’s what it’s all about for him.

“It’s not about money,” Diaz said. “It’s about world titles.”

I don’t know as much as I should about boxing. My wife and I cover the fights for various websites, but only because we like the sport. I like boxing history and theory but wouldn’t consider myself a great historian or anything. I’ll read a boxing book if I come across one that suits me, though, because I can’t help but read about these magnificent figures of sport.

As I watched Diaz spar that morning, I mostly wondered what he’d look like when he steps up past tomato cans like March 1 opponent Gerardo Robles. Diaz thinks he’ll be the same champion he was before, only smarter and more skilled. But fighters always think that. They have to. The minute they start believing otherwise is the minute their careers are over.

This is what I’m thinking about during the brief seconds between standing and staring at paintings at the museum. I don’t know many genres of art, but the Impressionists always seem to catch my eye. To me, they capture the beauty and the power of life but in a way that appears at once magical and realistic.

Take Renoir’s Sunset at Sea. Is this not what you’d see looking across the ocean at the glimmering majesty of the setting sun? But at the same time, isn’t this also completely unlike any picture even the most advanced camera could help you collect? To me, Impressionism is both less and more than life.

Diaz sparred eight rounds that morning. He went three against TV fighter Lanard Lane and five against local lightweight Danny Garcia. Diaz was aggressive but not stupid. His corner men, Derwin Richards and Timothy Knight, hurled instructions at him from across the ring, telling him more or less exactly that.

“Bend your knees,” said Richard. “Now turn…turn!”

“Keep that jab going,” added Knight. “Jab!”

Diaz did all these things, but he threw hooks and uppercuts to the body and torso of his opponent less like a man who wants to box smart and more like a man who just wants to be in a good fight. That kind of thing is what made him so popular in the first place, I suppose, but it was also his undoing.

But Juan Diaz is going to be Juan Diaz, and that’s something we could probably all learn from.

After witnessing the two Saturday exhibitions, Juan Diaz and The Age of Impressionism, I can’t help but wonder if Diaz will be able to pull off what the Impressionists did all those years ago. Reactionaries to the prevailing sentiment at the Salon, artists like Renoir have now become measuring sticks for others. No one who studies art skips over what they did during their time. And no one has forgotten them now that they’ve turned to dust.

In a similar way, our present culture’s Salon doesn’t think Diaz should be boxing anymore either. After all, they reason, Diaz has a college degree and several successful businesses. More than that, he’s smart, sharp and affable enough to get along better than most everyone else without trading punches in the ring for money.

So I think Diaz’s comeback might also be a reaction, one to the idea that men should only fight if they have no other way to earn, the one that says boxing isn’t suitable for Diaz now because he could make money doing other things. It’s as if we are to believe the dignity of a human being, the value of a soul, is something that can be measured by one’s capabilities or by how one chooses to make his way through the world.

Diaz rejects this premise. And who knows? Perhaps 150 years from now, some silly writer and his wife will roam around a museum on a Saturday afternoon to revere Diaz the way we did Renoir and the Impressionists.

I wonder what they’ll do that morning.