Guillermo Rigondeaux: At the start of an audacious run that might prove historic

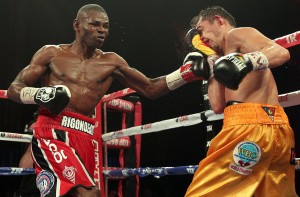

Saturday Cuban world champion Guillermo “The Jackal” Rigondeaux reduced Ghanaian super bantamweight and former bantamweight titlist Joseph King Kong Agbeko, no quotes, to an inactive and pacifistic mess, decisioning the African by extraordinarily unanimous scores of 120-108 (12 rounds to 0), 120-108 (12 rounds to 0) and 120-108 (12 rounds to 0). Agbeko, once the very picture of a volume-punching craftsman adept at stealing others’ wills, got uppercutted by Rigondeaux often enough early enough to throw a metaphoric white towel on the match at its halfway point and leave it there.

It takes a special sort of audacity to deploy an uppercut from range in a championship prizefight. Howsoever one chooses to throw it, the punch must begin with a hand perilously lowered, placing an unusual defensive onus on footwork. It is a punch one is taught never to throw moving forward, an instruction a young fighter needn’t hear more than once – hard enough as it is to switch his feet and body weight correctly to throw the punch even when it is a logical counter and available, like when a volume punching opponent repeatedly sets his chin over his front knee, as every volume puncher is wont to do whether by audacity, carelessness or necessity, and charges the uppercut, head lowered.

The uppercut is a punch rarely thrown accurately by the slower fighter in a match, and even more rarely thrown by slow fighters. When thrown as a back-hand counter, the punch needn’t travel far, relying as it does on the opponent’s weight and leverage – rushing into it and impaling his chin on the point of its middle knuckle – and the effectiveness of its shortened leverage can be taught a young fighter by nearly placing his back elbow on the face of its corresponding hipbone, and moving them as one, ensuring both a proper weight transfer and a necessarily restricted range of motion.

To throw the uppercut with one’s lead hand generally makes an up-jab of it, a narrowed glove whose thumb faces its thrower from trigger to contact, and ought be followed with a cross or something from the back else its thrower will expose himself unjustifiably. But to throw the back-hand uppercut as lead? That requires the audacity of a madman in the moment it is thrown, regardless of its employer’s precision. Juan Manuel Marquez used a right-uppercut lead to snatch the fighting spirit right out Rocky Juarez in their 2007 super featherweight match, sending Juarez dejectedly shuffling to his corner between rounds wondering how slow and classless he had to look to Marquez, during “Dinamita’s” mastery period and well before his reinvention-of-physique, to prompt the Mexican to consider such a lunatic ploy, much less snap his head upwards with it.

It was the very sort of audaciousness Guillermo Rigondeaux used against Joseph King Kong Agbeko, Saturday, in as one-sided a championship match as has seen a 12th round in years. It didn’t begin that way, either, and Agbeko, despite what Rigondeaux reduced him to, and despite his debut at 122 pounds coming in only his second prizefight since losing a rematch to Abner Mares 24 months ago, did not begin timidly as one recalls, either.

Agbeko, as high-class a volume puncher as the sport had in 2009, when he decisioned Vic Darchinyan and got decisioned by Yonnhy Perez – back when Agbeko’s aesthetically daring ringwalks included a gorilla mask, shackles and a blonde keeper, in a nod to the middle name, King Kong, Agbeko claims is written on a Ghanaian birth certificate probably having a different birth year than what “1980” Agbeko also claims – began the open of Saturday’s match in proper form, throwing a righthand lead or two at his southpaw opponent. Almost instantly, or at least instantly enough to overwrite in our memories what time passed before its appearance, Rigondeaux snapped a left uppercut from his southpaw stance, a back-hand uppercut counter, that snatched the fighting spirit from Agbeko with a frightful economy.

This was not a larger or stronger man unbuttoning a lesser man, a spent cutiepie American suddenly confronted by someone who hit harder and was quicker too, but rather an evenly matched champion unraveling a former titlist from Africa, a continent from which no prizefighter ever ran his way to America. Agbeko, the man who unmanned Darchinyan when the “Raging Bull” was finished stretching Mexico’s slickest boxer, Cristian Mijares, and Mexico’s toughest showman, Jorge Arce, three months apart, got stung three times by Rigondeaux in the fight’s second and third minute and spent what 33 minutes followed doing anything he could not to be stung again – and getting stung again and again.

Legend has it Joe Frazier said to a young Marvelous Marvin Hagler, “You have three strikes against you: You’re black, you’re a southpaw, and you’re good.” Aficionados looking for an explanation of fans’ and opponents’ continuing avoidance of Cuban Guillermo Rigondeaux – a man whose ancestors arrived in the Western Hemisphere the same way African Americans’ did – might take Frazier’s three strikes against Hagler and add a fourth: You don’t speak English. Something like this, though not exactly this, is what Rigondeaux alluded to in footage from an HBO prefight interview, Saturday, when he said all was always harder for Cuban fighters, men whose leader made a habit of making international laughingstocks of American leaders for about 50 years, because they did not need to get hit frequently as Mexicans.

Statements like that, actually, should benefit Rigondeaux, fighting as he does in a division populated with other Latinos, and subsequently lots of Mexicans – men whose aggressiveness and stylistic deficiencies mesh perfectly with the Cuban’s extraordinary offensive arsenal. Too, Rigondeaux should benefit from HBO’s patronage and promoter Top Rank’s matchmaking mastery. Provided he follows the course plotted him and stays what greedy impulses plague men, Guillermo Rigondeaux may well be starting the sort of five-year run, 2013-2018, that makes a prizefighter into a legend.

Bart Barry can be reached at bart.barrys.email (at) gmail.com