Looked like a Pacquiao Landslide, but the Math Says No it wasn’t

I did not score the Manny Pacquiao-Timothy Bradley Jr. fight two Saturdays ago. Having felt cheated out of a chance to be outraged like most everyone else last weekend, I decided to score the fight during its televised replay as part of HBO’s World Championship Boxing broadcast last night. In addition to tabulating my card for the first time, I decided to critique the cards of Duane Ford (115-113, Bradley), C.J. Ross (115-113, Bradley) and Jerry Roth (115-113, Pacquiao) on a round-by-round basis. My findings were somewhat unexpected.

I did not score the Manny Pacquiao-Timothy Bradley Jr. fight two Saturdays ago. Having felt cheated out of a chance to be outraged like most everyone else last weekend, I decided to score the fight during its televised replay as part of HBO’s World Championship Boxing broadcast last night. In addition to tabulating my card for the first time, I decided to critique the cards of Duane Ford (115-113, Bradley), C.J. Ross (115-113, Bradley) and Jerry Roth (115-113, Pacquiao) on a round-by-round basis. My findings were somewhat unexpected.

Firstly, my scorecard read 117-111 for Pacquiao. I gave “the Pride of the Philippines” rounds one through nine, marking rounds three, seven, eight and nine as rounds that could be argued for Bradley. I gave rounds ten through twelve to Bradley inarguably.

My biggest issue with folks that take umbrage to a “controversially” scored fight, is that they rarely take into account how many rounds in a given bout which could be scored for either fighter. Even though I had it wide for Pacquiao on my card, if Bradley had been given the benefit of my four close rounds, I would have had it 115-113 for Bradley.

The folks at HBO made analyzing the three officials’ cards easy, as in typical fashion, they displayed each judge’s card after each round. Having had four arguable rounds, those are the rounds where the judges could have had it for either fighter and I would not take a demerit against their final score.

Of the rounds I found to be poorly scored, Duane Ford had three of them, but one was actually a Pacquiao round I found to be puzzling – round eleven. Ford also had rounds one and five for Bradley. Counting Ford’s highly questionable rounds, it would be a one-point swing for Pacquiao, meaning in my eyes he should have handed in a card that read 114-114.

C.J. Ross called two rounds for the wrong guy, giving rounds two and five to Bradley. The two-point swing in favor of Pacquiao means this card should have read 115-113 for Pacquiao, not Bradley.

Jerry Roth missed the ball just once in my estimation, as he scored the second round for Bradley. This means his score should have been one round wider for Pacquiao at 116-112.

Boxing is a sport where winners are decided based on human interpretation, which means there is plenty of room for error. The Manny Pacquiao-Timothy Bradley Jr. WBO Welterweight title bout was not the worst scored fight of the century, decade or even this year. Four out of the twelve rounds could have been scored for either fighter, a swing which makes several final scores acceptable.

I may be in the minority, but in breaking down the scoring round-by-round, I find little fault with the three judges currently being put under the microscope. Ford, the most outspoken of the three in recent days, had the worst night, which he may have even realized by the time round eleven came around. But in the end, Ford is human and boxing is boxing. We’ve seen computerized scoring, such as in the Olympics, and I’d take Ford over that any day of the week.

- POSTSCRIPT

Speaking of human error, that applies to us the viewer as well. Many of us had an invested interest in the outcome of the June 9th bout. Whether it was our love for a national hero, our simple desire to see the two mega stars of the sport enter a ring against one another without a recent defeat on their record or financial – we watch fights with preconceived notions and emotions.

This past April I stood in a Las Vegas media room and heard Top Rank head Bob Arum tell his publicist he had Brandon Rios a winner on points over Richard Abril. I need no replay to tell me there is no way Rios should have left the Mandalay Bay with a decision win on that night. Giving Mr. Arum the benefit of the doubt, and let’s say his financial connection to a Rios win had no bearing on his card, than it must have been his preconceived expectation that Rios would win that swayed his opinion of the fight. Maybe that has a lot to do with his outrage this time too.

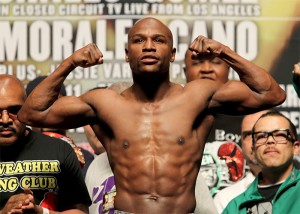

Photo by Chris Farina/Top Rank

Mario Ortega Jr. can be reached at ortega15rds@lycos.com.