Apropos of something entirely unrelated to “The One,” I spoke with Don Turner last week, a delightful man of gradual delivery and enviable authority, whose words set me to remembering, Saturday, others of his words spoken in 1996 before his charge, Evander Holyfield, undid Mike Tyson: Tyson can punch, but he can’t fight.

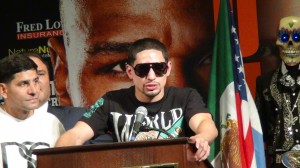

While it is wrong to write Argentine Lucas Matthysse can only punch, and a character-measuring abomination to compare Danny Garcia’s father to Turner, it is not improper to guess Angel Garcia’s wager in preparing his son for Saturday’s co-main event victory over Matthysse was not unlike Turner’s wager 17 years ago: Just as soon as he punches you, son, you punch him right back, and see if he freezes.

There are very few hard punchers of any kind, and particularly those who can bring unconsciousness with a single blow, that respond effectively to someone hitting them back; it’s a skill many never cultivate while racing through the professional ranks because each heavy punch of theirs that does land changes the man across from them completely enough to make for power punchers a habit of relaxing and stepping forward to drop a period at the end of their sentence or, just as likely, reread the sentence and enjoy their prose. Manny Pacquiao is an exception to this, and for that he was exceptional: He was a puncher who, if you punched him back as he attacked you, he punched you again, and so it went till he dropped you – as experienced by Juan Manuel Marquez in his second fight with Pacquiao and Miguel Cotto in his only fight with Pacquiao.

Far more common is the reaction Lucas Matthysse showed Danny Garcia, which was an inactivity not entirely dissimilar from what Tyson showed Holyfield whenever they engaged. The secret to stop a force like Matthysse or Tyson (or Gennady Golovkin) is to promise yourself the harder he hits you the faster you will leap at him. It is what Garcia did in Saturday’s meaningful fight – “The One,” as it were – each time Matthysse landed clean, whether with a right cross or left hook; Garcia followed his plan, resolute in a belief that if Matthysse was striking him hard, Matthysse was overcommitted and therefore open to be struck hard.

Each time Garcia did this, Matthysse bore a greater resemblance to Vic Darchinyan, taking a step back and adjusting his trunks and touching his gloves and readying for a next lunging collision, than what great fighters he’d enjoyed a plethora of comparisons to recently – despite completing 9 1/2 years of prizefighting without a world championship (Garcia won a world title in his fifth year, and Floyd Mayweather in his second). The fighting impulse Matthysse forced Garcia to show, yet again, was probably the evening’s most impressive sight, whenever Garcia found terms of engagement equally favorable and engaged Matthysse directly, though just barely.

The evening’s second most impressive sight was Floyd Mayweather, simply put. On the occasions Mexican Saul “Canelo” Alvarez struck Mayweather with a clean punch, and they were infrequent enough to be named and numbered, Mayweather did exactly as he’d done when Mosley buckled him in a rare moment of carelessness and Cotto brought the pugilist out of him in 2012: Mayweather took a traditional fighting stance, hands up, legs bent, and punched the hell out of the Mexican. That Mayweather rarely gets hit anymore makes a generation of casual fans think he cannot withstand contact when he is struck, and that is ridiculous in the strictest sense of the word – worthy of ridicule.

Alvarez’s greatest asset Saturday was not his red hair, though that was how he got the fight years and accomplishments prematurely, but the brittleness of Mayweather’s right hand. Had Mayweather a right fist structurally reliable as Alvarez’s, Mayweather would have stopped Canelo, and Canelo’s promoter six years ago. Which is not to discount wholly Canelo’s performance Saturday, for he did land that crisp lowblow in round 4 and a well-placed shoulder in round 6, but to compliment the inconsolable bent Alvarez showed in Saturday’s postfight press conference. It was the humble posture his performance demanded; no accusing Mayweather of running, no flashing that gorgeous smile and proclaiming a hunger to get back in the gym Monday, no appealing to ethnic loyalty – “nosotros, los mexicanos, sabemos quien realmente ganó” – but a headbent befuddlement fitted to the occasion of his undressing by a man who, despite having only one more prizefight on his resume, was approximately five times the sweet scientist Canelo is.

Here’s an appropriate place, too, for recognizing Paulie Malignaggi’s insightfulness during Saturday’s Showtime broadcast. Malignaggi has become that rarest of professional athletes: a man capable of saying something intelligent about a subject other than himself. Malignaggi caught every nuance of Saturday’s main event confrontation, sometimes speaking over what cloying salesmanship cluttered the evening – like a just purchased car barking at its new owner “how about that handling? you see how bright those headlights are? This is probably the greatest automobile purchase anyone ever made!” – to share, in an instant, what Mayweather did to provoke Alvarez’s lowblow in the fourth and thraw his attack during the other 35:55 of Saturday’s fight, minutes nevertheless more suspenseful than most Mayweather affords, because the man across from Mayweather was very much larger.

A larger opponent is the only way this “Money May” deal remains compelling, and so let us have no more talk of a fight with little Danny Garcia in May. Even casual fans now know no one can outbox Mayweather, no style makes him fight, and in order to get their $74 again Mayweather will have to find himself a middleweight.

Bart Barry can be reached at bart.barrys.email (at) gmail.com